Systems, Design, and Cost

The systems of a house

Tom Negaard

In order to spark fundamental change to the design of houses, we must ask ourself fundamental questions of what a home is and what its fundamental systems are. How universal is this collection of systems and have they evolved to create the modern-day Minnesotan single-family home? Identifying this group could help us re-frame our personal definition of a home while providing a baseline with which we can evaluate the evolution of the single family home in the United States.

It is easy to forget that Minnesota was once solely inhabited by humans who survived and thrived in temporary structures built from poles and stretched skin. The home has evolved and with it came expectations and systems which, though effective, have, in part, contributed to the large, isolated, and expensive homes of the modern day. Since the average US home has grown to that of excess - both of size and cost - a return to the fundamentals is necessary to enact change.

We established four categories for what a house provides to those who live in it: shelter, gathering, privacy, and comfort / ownership. Each category has a group of associated systems which manifest that idea (shelter, gathering, etc.) physically. We then compared this group to the most common terms new homebuyers look for in a house - including their associated systems.

What a house provides

A house provides physical protection from the outside world - including weather, animals, and other humans. How the home responds to these environments is site specific though the essence of protection is essential.

The house is also a place for gathering and living. By bringing people together to live in proximity and also providing hospitality to others. The home is a place to store, prepare, and share meals and a collection of systems are responsible for making that possible. It is also responsible for connecting other homes in proximity, creating, in essence, a community. The home promotes gathering and connection both within and outside of its walls.

The adverse of gathering is the benefit of privacy that the home affords. Separating and subdividing spaces within gives individuals or groups private (or semi-private) spaces inside of the home. The enclosure of the house externally privatizes its spaces and contents from the outside world. Other systems, such as plantings and sheer distance, isolate a home from other signs of humanity. Internally, it is mostly walls and openings which provide privacy to those who live-in and use a home.

Lastly, homes provide a level of comfort and ownership to its inhabitants. Ownership can come from the contents of the house - filling it with things that are your own, an inward / outward expression of uniqueness through customization, and /or the association of memories which give the home the sense of being “yours.” The ways in which we “claim” a home as our own contribute to the comfort of being in one’s home. Additionally, systems such as enclosure and thermal control create more habitable spaces and further protection of one’s self and property from external stressors.

What we look for in a house

The categories that new homeowners look for in a home differ from the terms which define what it is a house provides - if by nothing more than a name change. Each term has different connotations and inclusions than it’s “counterpart” on the left side of the diagram; though, the systems which manifest the term three-dimensionally are often similar or identical.

Size is an important consideration for homebuyers. A house needs to meet their needs in terms of both program and area devoted to each program. The area of the lot is also connected to this category. The “size” category expand upon the “shelter” category by placing importance on the contents of what is being enclosed - not simply the act of enclosing.

The location of the house places it in relation to green spaces, other homes, commercial centers, schools, transportation, and countless other spaces and places. The hierarchy of importance differs from person to person though there are systems (like roadways, sidewalks, transit routes, communities, etc.) which determine how successful the location is to the homeowner.

Privacy is connected to both the design of the home and its location. Walls and partitions / programmatic design provide privacy within the home while plantings, barriers, and location separate the home from other homes and the public.

The style and age of a home is important for homebuyer’s own preferences and budgets. Older homes may be less energy efficient and require more maintenance than a newer home. Newer homes might also have included amenities that drive up the price unfavorably. A home’s style has associated connotations and cultural connections which are important to a homebuyer’s decision.

Arguably the most important factor in choosing a home is price. Homes are most often the most significant investment a person makes in their lifetime; while the above factors range in importance, if the price is too high, a home can be unattainable. The price of a home, connected to the above systems, also gives back to those who own it in the form of equity. This is not included in the “what a house provides” diagram as it is not physical; though, it should not be overlooked.

The evolving American home

After re-examining and categorizing what makes our homes what they are, we must look at the evolution of the American detached single family home (DSFH) - as it is the affordability of this house type that this research is concerned. The DSFH was reinterpreted in the 20th century most famously by Sears, Roebuck, and Co., who sold simple and affordable kit homes to populate and iconize the expanding American suburb. Affordable single family homes were available to the masses. They were attainable, quick, and varied (though part of a limited catalog). The homes featured in Sears catalogs ranged in size from 600 - 1,500+ sq ft - with prices as low as $1.2 / sq ft - not adjusted for inflation (searsarchive.com).

Sears set the standard for affordable single family housing by using the kit home method to lower costs and increase efficiency. As the century progressed, there were continuous examples of designers, builders, and manufactures who used kit or prefabricated home processes to design and build affordable houses for the masses. These homes often had an associated architectural language - be they part of a notable development effort (Sears or Levittown) or designed with an aesthetic signature (Cliff May Homes). This type of home design and construction, although successful, has fallen out of favor with US home builders and buyers; in 2017, modular homes represented only 1% of new single-family houses completed (US Census). While the construction industry is slow to adopt new construction methods, the size and price of homes has changed dramatically over the last century.

While it is out of the scope of this research to examine and evaluate why US homes have ballooned to their current average size and cost., it is undeniable that American homes are huge - a comparison of average home sizes across Western countries shows as much. The average size of 2,265 sq ft for the Midwest (2,314 for the US as a whole) is a 71% increase in area from the 1950s national average and a 62% increase from the national average in 1910.

How building code shapes homes

The Minnesota Building Code establishes minimum program and size requirements for both habitable spaces and dwelling units. Our diagram lays out the required spaces and how small those spaces are allowed to be for an “efficiency dwelling unit”. Living rooms and bedrooms are considered “habitable spaces” - requiring a minimum dimension of 7’ in any plan dimension. They each have their own respective minimum areas. The smallest a living room can be is 220 ft2 - with 100 ft2 added for each additional person (beyond two) living in the dwelling. Kitchens are not bound by the 7’ dimensional constraint though they must maintain 3’ of clear space between counter fronts, appliances, and / or walls. The code does spell out what kinds of appliances (vaguely) are necessary in a kitchen - specifying each appliance have a minimum of 30” of clear working space. A similar list of requirements is included for bathrooms. Kitchens and bathrooms, though, do have restrictions on their ceiling height along with habitable spaces.

Habitable spaces have a minimum allowable ceiling height of 7’-6” while kitchens and bathrooms have a 7’ minimum. Closets have no restriction on dimensions. It is these five spaces which are required for an “efficiency dwelling unit” to meet code standards on program. There are additional code requirements for lighting, ventilation, and finishes. These requirements have all impact on the cost of a home and who / what is being constructed. Most homes in Minnesota are built to code both for safety considerations and fiscal security. Homes that are built to code are safer investments for lenders. For more information on building code, please see the GMRHP section on code.

Home-builders, home-buyers, and home-designers, need to think critically about what their definition of home is, and how much home they need, in a time of nationwide affordable housing shortages. Would young homebuyers be willing to purchase a $800 sq ft home with fewer of the commonplace luxuries (laundry rooms, air conditioning, etc.)? Would homebuyers be willing to off-load half of their shared living space to the exterior - creating a smaller home footprint in the winter and a much larger space for the other three seasons? Homeowners may be willing to accept less if the supply (and the price of said supply) reflected their needs. There is a serious demand for less expensive housing in the US and Minnesota, specifically. By continuing to critique our own definitions of “house”, we can question our assumptions and expectations - possibly arriving at a home that better fits an individual’s lifestyle and budget.

How do we make homes?

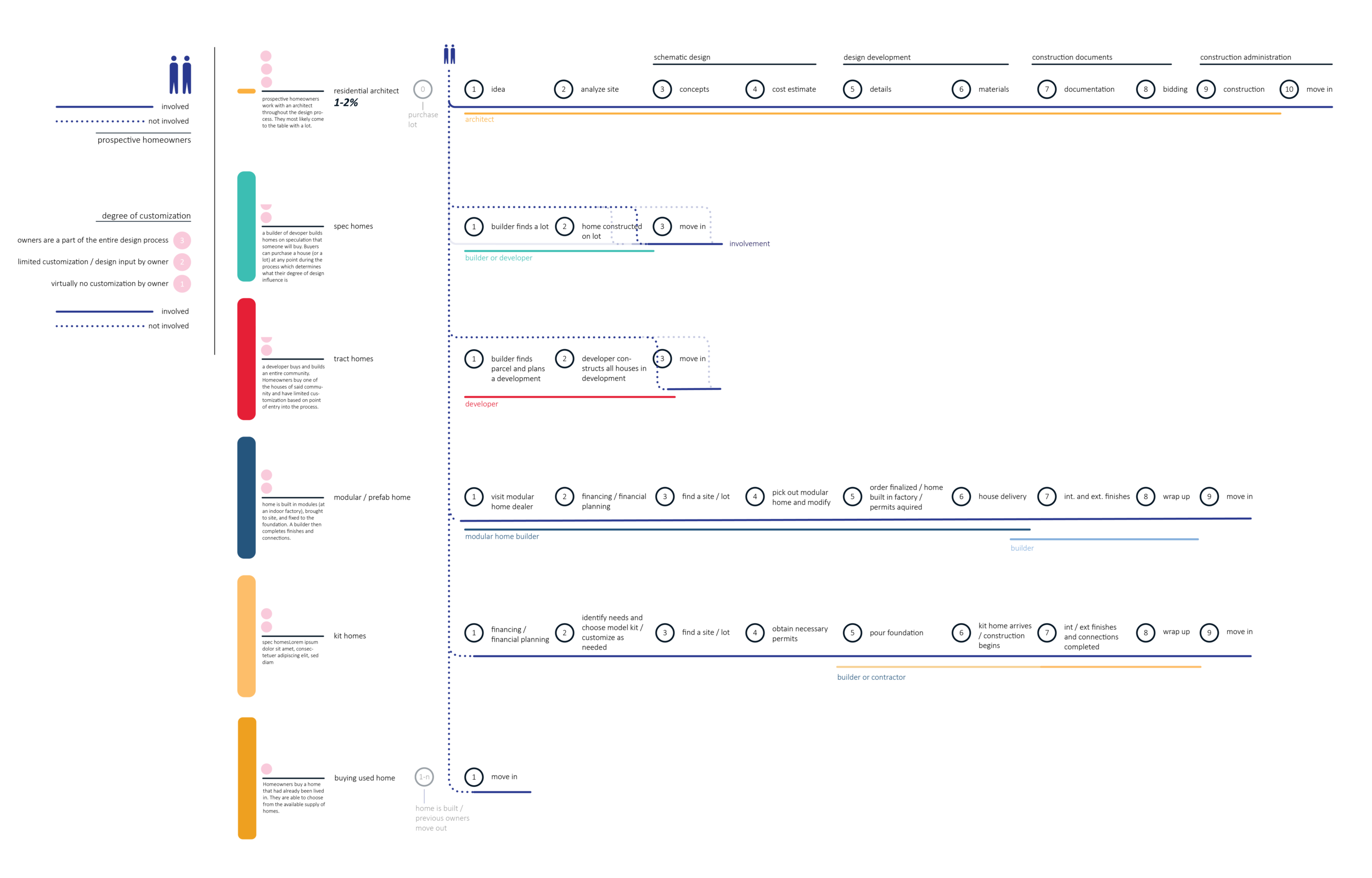

Some estimate only 1-2% of new homes built in the US are designed by architects. This process has become a luxury - reserved for only those who can afford it. A custom home takes time, money and involvement for both the home buyer and the architect. If working with an architect gives home buyers the largest input in the design of their home, then who is designing most of the homes built in the US?

Someone is making the bulk of the design decisions of the US housing supply. These decisions directly contribute to the size, efficiency, and cost of homes. Some processes involve the home buyers to varying degrees while others exclude them completely.

The diagram below unpacks six of the most common ways that we make and acquire homes. These processes vary in duration, cost, efficiency, and homeowner input - though they all end in the same place. The lengthiest, and most involved, process is working with a residential architect to design one’s home. By looking at the relative involvement and required steps, it is not surprising that this option comes at a premium. Architects work off of a percentage of the cost of construction and are invested and involved in each project. This codependency on cost and time has driven the architectural experience to those who can afford it. While homes built by architects are usually above average in cost, they are built to suit. Since the homeowner has been involved, they are receiving a home which has the size, amenities, and features they desire. As we move to other options, the new houses become more a function of what is available - leaving the home buyer at the mercy of the supply instead of customizing to their needs.

Spec and Tract Homes

Spec and tract homes are similar in that developers / builders are constructing homes with the assumption that a demand will exist. Home buyers can insert themselves into the process at any point though most enter towards the end of the cycle. At this point, the buyers are still able to exercise some influence over their new home - sometimes allowed to choose finishing details or appliances - though the bulk of the home was designed and built without them.

Modular and Prefab Homes

Modular and prefab homes are created, in part, in a factory then transported and assembled on site. They differ in the amount of manufacturing completed in the factory. Prefab homes often have finished walls manufactured off site then shipped and assembled on site. Modular homes complete much more of the building process off-site - often manufacturing entire rooms (or homes) in the factory, transporting them to the site, and attaching the units to a foundation / utility connections. The degree of customization depends on the method and company - though, customization is often limited as companies use standardization and economies of scale to increase efficiency. Spec and tract homes can be constructed using modular or prefab methods, though it is the interaction between the customer and the home builder which distinguishes the four.

Kit Homes

Kit homes are made from a collection of pre-cut parts and pieces is shipped to the site and constructed by either the homeowner or a hired builder. They can be more customizable though they are still edited from a selected catalog of home designs. A homeowner’s changes either go through the design firm - who edits the amount of parts sent to site - or the homebuilder - who changes the design upon construction.

Used Homes

Finally, buyers can buy an already built and lived-in home. This is the most common way people acquire a home; in 2019, 6 million homes were sold in comparison to 1.2 million homes constructed. The house could have been built using any of the previous methods but that has no impact on the timeline of the new owner’s purchase. The fastest (relatively) way to acquire a home, the buyer has to choose from what is available but forgoes many of the hidden costs and extended timelines associated with building a new home.

There is a disconnect between who is designing the majority of US homes and the needs / wants of those looking to build or buy. There cannot be meaningful change to the design (and, by extension, cost) of homes if home buyers continue to vote with only their dollar. If the barriers to entry were lower, designs were open-sourced, and architects / designers were destigmatized as too expensive, there could be a clearer dialogue between demand and supply of US homes.

The cost of homes

Arguably the most significant factor in the consideration of buying or building a home is money. The average cost of a US home has gone from $3,200 ($81,000 adjusted for inflation) in 1915 to over $260,000 in 2020. In Minnesota, the average home price has grown to over 4x the median household income (MinnPost). Some contributors to these increased costs are materials, labor, regulations, and land.

Tariffs and demands on lumber have stressed the wood industry and contributed to increased materials costs. (MinnPost) Additionally, costly high-tech extras are being added to more homes. There is a workforce shortage in the home construction industry. Contractors are forced to pay higher wages to keep and retain workers (MinnPost). Regulations also impose cost burden on new and existing homes - even if they are meant to make homes safer and more efficient. Lastly, the price of land has steadily increased, and with it, the cost of ownership. As rising costs make homes less attainable, cultural decisions are also affecting the supply of homes.

A Shift in Demographics

Following the 2008 financial crisis, home buyers are consistently “buying down” and opting to move less (MinnPost). These trends take more affordable homes away from the income bracket most appropriate for them. A resistance to move also lim- its the supply of available housing. The relationships of these interconnected factors beg the question, how is the cost of a home broken down?

Cost Breakdown

The National Association of Home Builders collected and categorized the different variables which create the total cost of a home (Figure 12). Of the total, construction (55.6%) and finished lot cost (21.5%) have the largest shares. The construction piece was further broken down into sub-categories which contribute to its 56% stake. Interior finishes are the single largest contributor to the construction cost, though there is not a significant drop off between subsequent categories.

Cost of Home Construction

Construction Cost Breakdown

A New Tool

As helpful as it is to see the cost of a home subdivided into percentages of a circle, a more helpful tool would be an interactive one - where designers, builders, or buyers could make decisions and see those choices reflected in the (estimated) cost of their home. Our interactive model can afford more transparency in the costly design - build process and potentially encourage conversations around what is and is not necessary in a buyer’s new home.

The interactive cost model, diagramed in Figure 14, begins with user input on size / number of rooms in their desired house. The categories are derived from the most common spaces in US homes. When the user changes an input (adjusts the number of bedrooms from two to three, for example) a new total square footage is calculated for the house. This is then multiplied and summed with a series of other costs which are directly connected to the square footage of the home (materials, framing, finishes, foundations, etc.) The user can then input the cost of their lot and adjust the cost per unit area to land- scape. Further costs, such as permitting, financing, and profit, can be linked to the home’s footprint or total cost to provide a more accurate cost profile of the home. With the tool, a user’s decisions will, in real time, generate an estimated cost and size of their prospective home.

Community assets can also be leveraged in the building of homes. Not only can this lower costs but it can foster a sense of ownership by the community and its members. The cost model can be linked with a similar model that measures the assets of a particular community and weighs the impact of their involvement on the construction cost of a house (Figure 13). This type of integration is the next step for this project’s interactive model.